ABSTRACT

Authenticity, in the sense of credibility or truthfulness, is one of the key categories of heritage management. This paper deals with the issue of authenticity in relation to industrial heritage, specifically water management structures. In the case of these structures, emphasis is usually placed on the authenticity of function, but two further types of authenticity are equally important: authenticity of material substance or form (in relation to the original design and the structure built on its basis), and, on the other hand, authenticity as a consequence of historical development. This paper presents an analysis of four model examples of water management structures that are either legally protected heritage sites or have been proposed as candidates for heritage protection. The analysis of their heritage values provides insights into the individual categories of authenticity and enables the formulation of principles for managing sites of heritage value.

INTRODUCTION

One of the most challenging heritage management categories to grasp is represented by the issue of authenticity of monuments in the sense of their credibility and truthfulness. Defining the concept and setting sub-categories is essential for the determination of the approach for monument management and is the subject of long-standing discussions among experts. This was inspired by a book called Moderní památková péče (Modern heritage protection) from 1903 written by Alois Riegl [1].

Petr Kroupa explains two basic principles of heritage management via the relationship between authenticity and time: “With the emergence of practical heritage management in today’s sense, two basic and diametrically opposed concepts have clashed in practice and in theoretical reflections on monuments to this day. The first one is based on the appreciation of traces which time has left on the original material of a work and demands them to be respected. The other one regards a fully-fledged life of a work of art only in terms of the ‘authenticity’ of its historical substance (i.e. in the form released from the artist’s hands at the time) and demands traces of the elapsed time to be deleted and the initial integrity of the work to be restored” [2]. These two approaches, analytic and synthetic, pervade the history of heritage management and are essential for both heritage assessment and authorisation of the level of intervention and determination of methods for the management of monuments, which involve conservation, restoration, renewal, or reconstruction (in the sense of renewing extinct structures, parts and elements).

Following these two approaches, Kroupa also distinguishes these forms of authenticity:

- Authenticity which is linked to the creation of the work: authenticity of the place of creation and environment, authenticity of forms created in historic time (i.e. in the time frame from its creation to its completion), authenticity of the modification of the surface form, authenticity of the creative idea, authenticity of function, material and expression (i.e. aesthetic effect).

- Authenticity of the life of the work, i.e. how it is connected with the time elapsed since its creation: authenticity of historical transformations of material substance, authenticity of age, and authenticity of historical transformations of function [2].

It is obvious from this overview that authenticity can acquire many sub-forms which may, or may not, be represented in individual cases and that some of them can even contradict (authenticity of material and authenticity of historical transformations of material substance, authenticity of function and authenticity of historical transformations of function, etc.). Heritage management most often deals with the authenticity of material and authenticity of form.

In the international context, the formulation of general criteria of authenticity is related to the need to set unified conditions for the inscription of monuments on the World Heritage List. In this context, in the 1970s, the authenticity of form, material, method, and environment was set as the basic one [2, 3]. Efforts at specification and elaboration resulted only later in the extension of the term by other categories. A document on authenticity from 1994 mentions form and design, materials and material substance, use and function, traditions and methods, location and environment, spirit and feelings, and other internal and external factors in connection with authenticity [4].

The complexity of the issue of authenticity takes on new dimensions in relation to industrial heritage. But individual categories of authenticity remain valid. As in the case of traditional assessment, the emphasis is put on preserving everything in its original unaltered condition (not affected by degrading modifications). Nevertheless, even a series of gradual modifications related to the technological development of the particular field can also be valuable [5]. The criterion of the authenticity of function is an important factor because objects of technology or of industrial heritage deprived of their purpose, first, become non-transparent (with the loss of the knowledge of the given technology) and, second, are doomed to extinction. Conversion, i.e. transformation of objects to find a new use for them, is usually associated with significant interventions into the authenticity of their material and form.

The first two methodologies also deal with the question of evaluating factors of heritage management in relation to industrial heritage. The first general Methodology for the Evaluation and Protection of Industrial Heritage from the Perspective of Heritage Management [5] deals with general issues: what industrial heritage is, how it should be evaluated and protected from the perspective of heritage management, and what measures can be taken in order to preserve it for the future. The issue of evaluation is crucial, especially as far as specific categories are concerned, which can be as valuable or even more valuable than traditional evaluation criteria. The main criteria for evaluation are as follows:

- typological value (taking into account whether it is an early or late use, wide-spread type or unique solution),

- value of technological flow (assessing a set of key operations, represented by specific objects or technologies, which ensure the production process from raw material input to the final product),

- value of systemic relations, which deals with the position of the object or technological flow within wider transport or production relations.

At the same time, it transfers traditional evaluation categories (architectural, urban, art-historical, value of age and authenticity) into the field of industrial heritage. Similarly to the traditional objects of interest of heritage management (architecture, painting, sculpture), the evaluation of industrial heritage distinguishes between the authenticity of the original state (in the sense of the initial project and its realisation) and the authenticity created by gradual development, formed by quality-valuable changes and modifications closely related to the development of the field [5].

The follow-up Methodology for the Classification and Evaluation of Industrial Heritage from the Perspective of Heritage Management – Water Management [6] was created in cooperation with several institutions: TGM WRI, the National Heritage Institute, Palacký University in Olomouc, and the Institute of History of the Czech Academy of Sciences. It presents a clearly arranged typology of the most significant water-management fields as a basis for the orientation in the topic of water management, and applies evaluation criteria for water-management structures [6].

METHODOLOGY

During the preparation of both methodologies, a wide range of examples of heritage protected structures and of their renovations and conversions was gathered, which can be analysed in terms of the evaluation of their authenticity. For the purpose of this text, model examples of heritage protected water-management structures or structures proposed for protection have been chosen, which are evaluated in terms of heritage sub-values, including authenticity.

RESULTS – OVERVIEW OF MODEL EXAMPLES

Prague, water treatment plant in Podolí

The water treatment plant in Prague-Podolí was built in two stages from 1923–1929 and 1952–1965 (Fig. 1–4). The author of the architectural design was architect Antonín Engel, while structural systems of the older part (northern hall) were designed by Bedřich Hacar and František Klokner. Both stages are linked together by characteristic monumental architecture whose surface is rendered in traditionalistic morphology, typical for Engel, and modern construction principles.

At first, water was collected from a river and three wells and treated with the triple sand filtration of the Puech-Chabal system. Methods of treatment were soon improved in connection with the transition from the production of non-potable to potable water by the introduction of a coagulation line (1931), the Wabag system (1943), etc. At present, two-stage separation technology is used. Only filter field casings remain from the original technology [6–8].

The value lies at architectural and urban level, in the value of the technological flow and functional complex (the process contains all elements of water treatment technology). The authenticity of function and, in relation to the construction fond, the authenticity of form and material, are also preserved.

In the benchmark study of water industry structures (including waterworks, sewerage, and wastewater treatment), it was presented as one of fifteen model examples representing universal values of world heritage, especially regarding the expressiveness of architectural forms and progressive construction systems as an expression of the contemporary significance of waterworks structures [9].

Fig. 1. Prague Podolí water treatment plant, north part (Photo: M. Ryšková, 2022)

Fig. 2. Prague Podolí water treatment plant, filtration hall, current condition (Photo: PVK Archive, 2018)

Fig. 3. Prague Podolí water treatment plant, filtration hall, current condition (Photo: PVK Archive, 2018)

Fig. 4. Prague Podolí water treatment plant, clarifiers (Photo: PVK Archive, 2018)

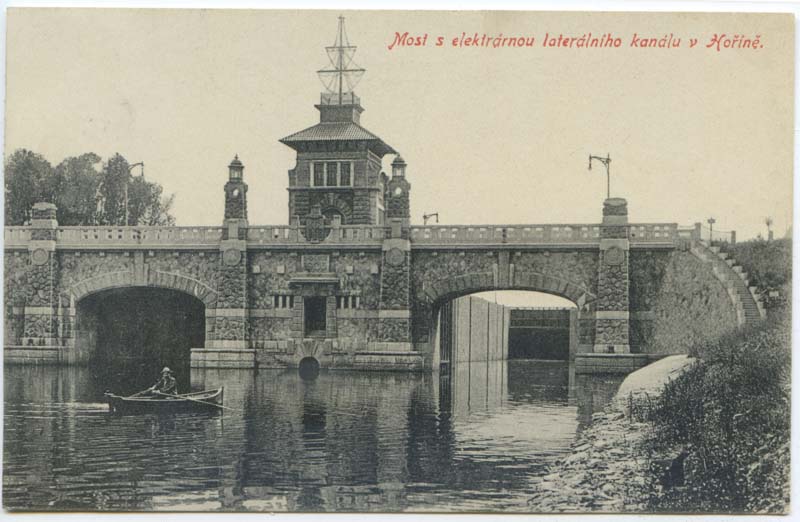

Hořín lock

Hořín lock was built from 1903–1905 as part of the lateral canal of the Vltava river, which was to ensure the navigability of Vltava to Prague (Fig. 5–9). Its aim was to equalise the ten-metre height difference between Vraňany and Hořín. It consists of a small and a large lock chambers and there are two bridges with segmental arches over the lower lock head (Fig. 5). The author of the architectural design was František Sander and of the technical solution, Antonín Smrček. The construction was carried out by the Lanna company. The expressiveness of the architectural rendering is based on the concept of the imaginary gate of the Vltava river, and it can be traced in other similar structures too; a parallel can be found, for example, in a lock chamber in Viennese Nussdorf by the architect Otto Wagner [6, 10].

Fig. 5. Hořín, lock chamber of a lateral canal of the Vltava river

(historical postcard, author’s collection)

Fig. 6. Hořín lock, new moveable bridge (Photo: O. Hrdlička, 2021)

Fig. 7. Hořín lock, new moveable bridge (Photo: O. Hrdlička, 2021)

Fig. 8. Hořín lock, situation after modification of the right large lock chamber and replacement of the bridge over it (Photo: M. Ryšková, 2021)

Fig. 9. Hořín lock, view from Mělník chateau (Photo: M. Ryšková, 2021)

In order to ensure sufficient parameters for the navigation of large passenger ships, as well as oversized cargoes and taking into account commitments of the Czech Republic within the European Union regarding the navigation of waterways, from 2019–2021 the lock was rebuilt: The bridge over the lower lock head of the large lock chamber was replaced, both lock heads were extended, and a new gate was installed. In connection with the large lock chamber being extended by 1 metre and the original underpass height being increased to 7 metres, the original reinforced concrete bridge frame was replaced by a steel truss frame whose elevation is ensured by hydraulic pistons [6, 11].

The value of the work lies at the architectural, urban, and technical level, as well as in its position within the functional complex of the lateral canal. The authenticity of function has been preserved at the cost of the loss of the original supporting structures of one of the two lock chambers, and thus also at the cost of disruption of the form and material substance of the work as a whole. A negative impact on the northern facade, visually oriented towards Mělník, lies in the disruption of the symmetrical composition, which is, from the visual point of view, significantly mitigated by transferring the original stone cladding and architectural details to the new structure (and adding the cladding while maintaining the material and the way it is processed).

Písek, New bridge, cylindrical weir, and hydroelectric power plant

A bridge with a cylindrical weir was constructed from 1938–1943 and a power station from 1948–1957, according to the project of architect Adolf Beneš. The power station was equipped with a Kaplan turbine from Šmeralovy závody, n. p., in Brno, with an output of 494 HP, and it was put into operation in 1951 (Fig. 10–11). As part of modernisation, the switch and control rooms were replaced while the generator with the excitation system and the Kaplan turbine have been preserved [12, 13].

Fig. 10. Písek, New bridge, cylindrical weir, and hydroelectric power station, overall view PÚ, ÚOP České Budějovice)

Fig. 11. Písek, cylindrical weir (Photo: J. Drozda, NPÚ, ÚOP České Budějovice)

The set of the cylindrical weir, power station, and bridge is important from the architectural, urban, typological, and technical points of view. In addition, it is a preserved functional complex which increases the sub-values of its individual parts as a monument. The typological value is associated with the cylindrical weir, which is one of only a few weirs with this structure in the Czech Republic. The authenticity of function and the authenticity of the original form and material in terms of construction and design have been preserved. The authenticity of the equipment of the hydroelectric power station is reflected in the requirements of contemporary operation. The replacement of the switch and control rooms is a compromise which is applied to heritage protected hydroelectric power stations as well.

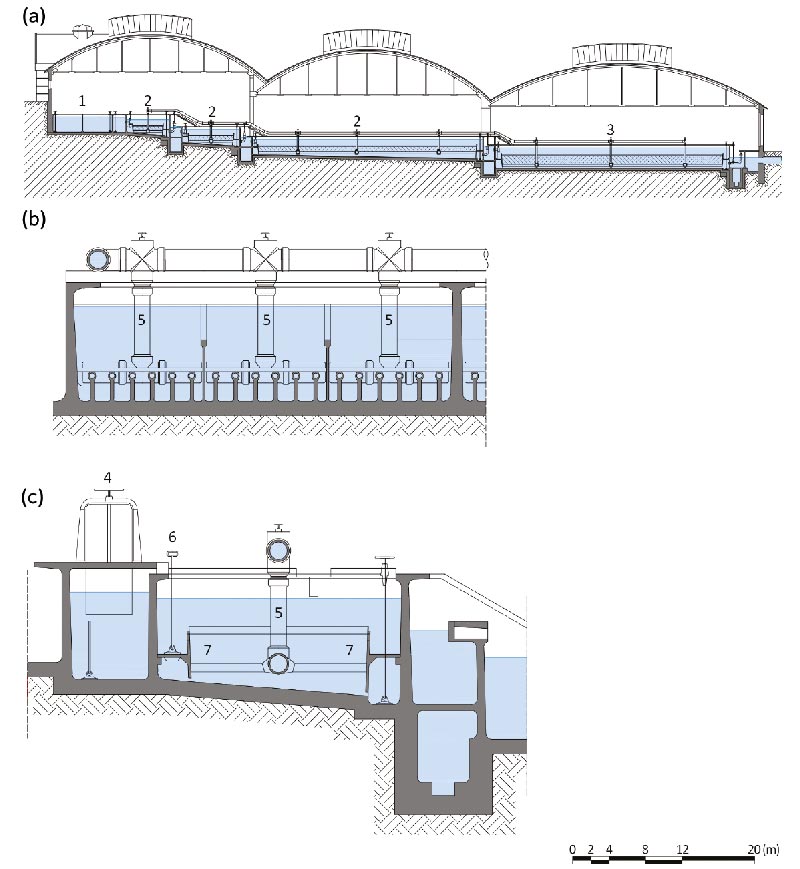

Plzeň, municipal waterworks filtration

The industrial development of Plzeň led to the construction of new municipal waterworks, which were put into operation in 1889–1890. Problematic water quality resulted, as early as 1908, in negotiations with the Paris company Puech-Chabal about the construction of a new filtration station (Fig. 12–14). Construction was carried out from 1924–1926. The filtration station, with a total area of 5,000 m2, was equipped with three stages of roughing filter with so called upper washing, i.e. washing impurities off the surface, and one layer of pre-filters. The author of the architectural design was Plzeň architect Hanuš Zápal, and construction was carried out by Prague company, Müller a Kapsa. The filtration process was completed by older slow filters and, in 1933, coagulation and chlorination processes were added. When operation terminated in 1997, the filtration building was preserved and, since 2015, it has been used as a fish storage tank. Gravel and sand were extracted from some pools and the original piping was used for the central distribution of air. In accordance with regulations and requirements of the Regional Veterinary Administration, an operational corner was installed [6, 14–17].

Fig. 12. Plzeň – Puech-Chabal filtration station: A – cross-section of the filtration building; B, C – longitudinal and cross-section of the roughing filter of the 1st stage, 1 – reservoir, 2 – roughing filters, 3 – pre-filters, 4 – sluice gate, 5 – blowing pipe, 6 – cleaning flap, 7 – hydraulic gate. Diagram by Radek Míšanec, 2022, according to: Pamětní spis Vodárna města Plzně (Commemorative file, Plzeň municipal waterworks), 1926; diagram created for the publication Methodology for the Classification and Evaluation of Industrial Heritage from the Perspective of Heritage Management – Water Management)

Fig. 13. Plzeň – Puech-Chabal filtration station, interior (Photo: M Ryšková, 2019)

Fig. 14. Plzeň – Puech-Chabal filtration station, exterior (Photo: Michaela Ryšková, 2019)

The filtration station of the Puech-Chabal system represents the so-called fourth era of waterworks systems and, in the territory of the Czech Republic, it has been documented only in three constructions: in the waterworks of the Psychiatric Hospital in Prague-Bohnice (1925); in the municipal river waterworks in Plzeň (1924–1926); and in the waterworks in Prague-Podolí (1922–1929). In 1943, the waterworks in Podolí replaced the Puech-Chabal filtration via the introduction of the Wabag system. In Bohnice, the filtration system was decommissioned in 1972 and the filters were filled in with soil. The Puech–Chabal filtration of Plzeň waterworks therefore represents the only preserved example of this system in the Czech Republic [6].

Its value lies mainly in the typological importance and in the authenticity of material and form, in terms of both technology (filtration system) and construction (including a number of original structures and also details – paving, tiling, mosaics). The function of the structure has been changed.

DISCUSSION – ANALYSIS OF MODEL EXAMPLES

Water management structures usually fulfil the functions for which they were built and rarely are they used for other purposes. The preservation of the authenticity of function is conditioned by modifications, necessitated in particular by changes in technology, increasing performance requirements and other parameters, or changed requirements for safety, hygiene, etc. These modifications are legitimate tools for maintaining functionality [6]. Selected model examples confirm these principles. They differ in terms of the impact on other forms of authenticity and heritage value.

The superiority of the authenticity of function does not imply being subjugated to other forms of authenticity. On the contrary, heritage management must precisely judge other values of the work and aim for a compromise acceptable to both parties – both operators and heritage protection.

Monuments must also be considered as evidence of the time in which they were created, in a wide range of meanings. In the case of industrial heritage, these are mainly examples of the development of individual technical or production fields. Therefore, the evaluation of typological significance must be accepted as the key one. In practice, it means the individual aspects to be included in the typological development of the field. The value naturally increases with the authenticity of material and form, which carry in themselves direct information on the constructions and materials of the time, as is shown in the example of the unique preserved Puech-Chabal filtration in Plzeň municipal waterworks. Only exceptionally is it possible to combine the requirements of the operation or (new) use with the typological characteristics as appropriately, as occurred in this case.

In contrast, in the case of the waterworks in Prague-Podolí, the authenticity of technology is a result of development. The process of its changes can be perceived as a sequence of qualitative valuable improvements which document a gradual improvement of the water treatment process, which occurred in the 20th and 21st centuries. Current technology will be evaluated in the future as one of the stages in water treatment development. On the other hand, due to the extraordinary architectural value of the original design and its realisation the authenticity of construction is related to the creation of the work.

The lock in Hořín is an example of a compromise which tries to mitigate the effects of the superiority of authenticity of function over other forms of authenticity and other heritage values. Adaptation to the size of current vessels has been resolved by modification of the lock chamber and replacement of the bridge over it. The new steel structure of the bridge departs from the authenticity of material and, also, partially from the authenticity of form. Its goal is mainly to preserve architectural values of the work. a negative impact on the authenticity of the work as a whole is mitigated by preserving a smaller lock chamber including its bridging in the current form.

The significance of the typological value and its close connection to the value of authenticity can be documented by the example of the cylindrical weir in Písek. This is one of only a few cylindrical weirs in the Czech Republic. The weir cylinders are outdated and a study of a planned renovation aimed for the replacement of the weir structure with a simpler contemporary solution in terms of operation, with the assumption that from a visual point of view this change will manifest itself only to a limited extent. However, heritage value and authenticity are not only connected to the external appearance and any change would have a crucial impact on the heritage values of the work: typological value and authenticity of form and material. If it is not possible to preserve the original elements due to their wear and tear (and in the case of cylindrical weirs these elements especially involve riveted cylinders), their replacement with copies of the original elements should be an adequate substitute. Although replacement causes loss of the original material substance, authenticity of form remains preserved, which is also evidence of a construction type preserved in only a few cases.

CONCLUSION

The heritage value of each item or of a whole is always a set of sub-values. The value of authenticity, which involves various forms, is one of the key values. Although, in the case of water management structures, it is the authenticity of function which is accentuated, it is also important to consider and protect its other forms which, in particular, include authenticity of material substance or form in relation to the primary project and its realisation, or authenticity as a result of historical changes, which occurred during its use.

Nevertheless, in terms of the meaning of the word “authentic”, i.e. “truthful” or “credible”, it is necessary to refuse such interventions in the essence of the monument which unjustifiably – for example to simplify operation or due to the poor condition of the object – destroy authentic material or form, arguing that this change will not visually manifest itself. Equally unacceptable in principle are shape imitations whose goal is to hide such changes or to resemble extinct forms. To put it simply, authenticity of monuments cannot be preserved when new materials and constructions are used and when “preservation” of the original form is only external. It is better to prevent serious disrepair through regular maintenance and partial repairs, which will prolong the life of the work and prevent costly total renovations and reconstructions.

Therefore it is necessary to weigh the legitimacy of each intervention and the level of its impact on heritage values as a whole. If a change cannot be avoided (e.g., it is provoked by safety requirements or to maintain function), then it must be accepted as a new layer in the “life” of the work, as another of its historical transformations. Construction changes can be made in such a way that a new, visually recognized layer is created in the development of the work, comparable in quality of design and execution to older layers. Exceptions may be cases where the necessary change of a constituent part would have a fatal impact on other heritage values of the work as a whole and the goal is the mitigation of this impact.

In the case of technical equipment, key elements or selected representatives can be left in place after decommissioning as a reminder of earlier phases of development, or they can be deposited in a relevant museum.

Acknowledgements

Special thanks to territorially specialised departments (ÚOP) of the National Heritage Institute in České Budějovice and in the Central Bohemian Region, Prague Waterworks Museum, Ing. Otakar Hrdlička and PhDr. Jiří Chmelenský for the documents provided and consultations.

This paper has been created within the research project DG18P02OVV019 “Historical water management objects, their value, function and significance for the present”, financed by the NAKI II programme of the Ministry of Culture of the Czech Republic.

The article has been peer-reviewed.